THE HOUSE OF WISDOM

The House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah) was one of the most influential institutions in the history of science and learning. Founded in Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate, it became the golden light of intellectual activity in the Islamic world. Scholars of different faiths and ethnic backgrounds worked side by side in this unique institution, translating, preserving, and developing knowledge from Greek, Persian, Indian, and earlier civilizations. The contributions of the House of Wisdom were not limited to the Islamic world alone. Through translations and scientific exchanges, this knowledge gradually reached Europe, especially from the 12th century onward, at a time when much of Europe was experiencing what is often referred to as the “Dark Ages.”

While the exact date of its founding is not completely clear, most historians agree that the House of Wisdom was formally established during the reign of the Abbasid Caliph al-Ma’mun, around the year 830. However, the idea of creating a major learning centre in Baghdad seems to go back earlier, to the time of Caliph al-Mansur (754–775), when the city itself was founded and the first scholarly activities began to take shape.

Baghdad was chosen to host the House of Wisdom for several strategic reasons. When the Abbasid Caliphs took power in 750 AD, they moved the capital from Damascus to this newly founded city. Located between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Baghdad stood at the centre of major trade routes that connected China and India to the Mediterranean. Because of this, the city quickly became a meeting point for people, goods, and ideas from different parts of the world. Persian administrative traditions, Indian mathematics, and Greek philosophy all came together in Baghdad. Unlike the previous capital, which was more connected to the Mediterranean world, Baghdad focused on the East and drew heavily from the rich intellectual traditions of Persia and Asia.

However, the real game-changer was a piece of technology: Paper. Just years before Baghdad was built, Muslim forces encountered Chinese papermakers at the Battle of Talas. They brought this technology back to Baghdad, replacing expensive parchment and brittle papyrus. Suddenly, knowledge could be mass-produced, transforming the House of Wisdom from a mere library into a “factory” for books.

The foundation idea of the House of Wisdom was closely linked to the rich cultural environment of the Abbasid period. The Abbasid state had a highly multicultural structure where people of different ethnicities, religions, and traditions lived together. Arabs, Persians, Syriacs, Indians, and Byzantines interacted within the same cultural space, which allowed different knowledge traditions to meet and influence one another. In addition, the strong emphasis that Islam places on knowledge and learning played an important role in the development of such institutions. Knowledge was seen as valuable and seeking it was considered a virtuous act. The financial and political support given by the rulers to scholars and translation activities also accelerated this process. As a result, the House of Wisdom became not only a scientific centre but also a meeting point for different cultures and ideas.

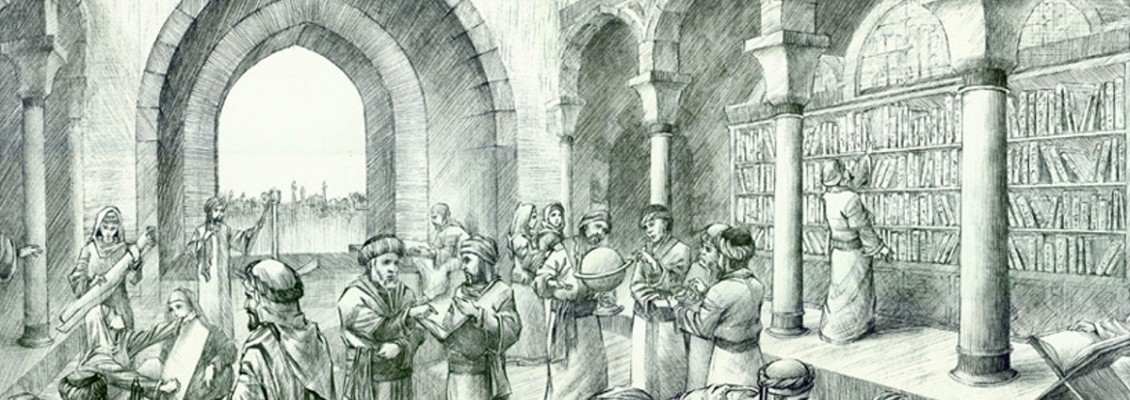

The House of Wisdom served many different functions, both as a physical space and as a center of learning and ideas. First, it worked as a major library where the knowledge of earlier civilizations was preserved. Manuscripts were kept here, carefully copied, and reproduced by scribes. Because it was such an important source of knowledge, scholars from different regions travelled to the House of Wisdom to study and gain access to these works. Over time, this turned the House of Wisdom into a major centre for reading and education. Scholars were provided with everything they needed, including reading rooms, classrooms, and materials for studying, translating, mapping and so on.

The translation movement in the House of Wisdom was especially crucial for the transmission of knowledge not only to the Islamic world but also to the West. Its foundations were laid during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd (786–809), who strongly supported scholarship and the collection of books from different civilizations. During his time, important works in medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy were gathered from Greek, Persian, and Indian sources. This movement reached its peak under his son al-Ma’mun, when translation became a large, organized effort.

Skilled translators such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq, Thabit ibn Qurra, and many others played a central role in this process. They translated major works of figures like Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen, and Ptolemy into Arabic with great care and accuracy. These texts were not only translated but also studied, commented on, and further developed by Muslim scholars.

Centuries later, many of these Arabic works were translated into Latin in places like Andalusia and Sicily. European scholars flocked to these cities, not to find Greek texts, but to find Arabic ones. Europe gained access to ancient knowledge that had been preserved and expanded in the Islamic world. They spent decades translating these Arabic manuscripts into Latin, reintroducing Europe to its own intellectual ancestors. In fact, for centuries, European universities taught medicine using Latin translations of Arabic textbooks, and they read Aristotle through the lens of his Arabic commentators. This transfer of knowledge deeply influenced the development of Western science, medicine, and philosophy and helped pave the way for the Renaissance.

Leave a Comment